Guest post by Joann Stevens

(Read previous post: Venerable Mary Lange)

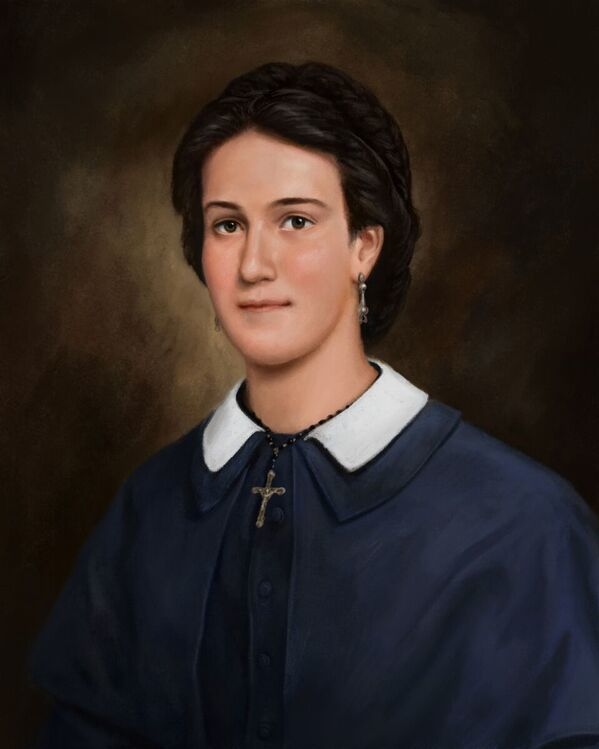

Venerable Henriette DeLille (1812–1862) was portrayed by actress Vanessa Williams in The Courage to Love, a romanticized, historical drama that highlighted the Quadroon Balls and system of plaçage that DeLille and generations of her ancestors were born into and practiced. Accepted in North American French and Spanish slave colonies, plaçage allowed wealthy White men to live double lives—one as a committed family man with a White wife and children on a plantation, the other in a household with a mixed-race concubine and children. These unions could last for a year, decades, or until death.

DeLille was a fourth-generation free woman, born and raised under plaçage. Despite a complexion so light that she could have easily passed for White, she never opted for this as the rest of her family did. She entered into plaçage for a short time and bore two children who both died in infancy. By her early 20s, DeLille’s deepening faith and encounters with God compelled her to reject plaçage and encourage other mixed-race women to do likewise.

DeLille wrote in French on the flyleaf of a book centered on the Eucharist, “I believe in God. I hope in God. I love. I want to live and die for God.” Her work on behalf of God is evident in the religious order she founded, Sisters of the Holy Family, and the historical New Orleans Tour the order created to educate people about the life and works of their foundress and order. (The Sisters of the Holy Family are the second-oldest surviving congregation of African American religious, with the oldest being the Oblate Sisters of Providence founded by the Venerable Mary Lange.)

Using funds from the sale of property, her inheritance, and loans, DeLille created programs to teach Black children the Bible and academics, founded the first Catholic home for the elderly in the United States, and fed and cared for the poor.

In 1881, the order purchased the Orleans Theater property that includes the former Orleans Ballroom, the site of the Quadroon Balls, converting it into a school and convent, with the ballroom itself serving as the chapel for the sisters.

Sources:

- Christine Schenk, “Venerable ‘servant of the slaves’ bears witness to how Spirit blesses faith,” National Catholic Reporter, Feb. 20, 2014.

- Josephine Dongbang, “Black Americans on the Way to Sainthood: Henriette DeLille,” St. Charles Borromeo Church, Feb. 13, 2021.

Julia Greeley (c. 1840–1918) was born into slavery in Hannibal, Missouri, sometime between 1833 and 1848. She came to Colorado to care for the family of first territorial governor, William Gilpin, and it was here that she became known as Denver’s Angel of Mercy and Missionary of the Sacred Heart. Greeley’s life and legacy align with that of the unnamed woman that Jesus recognized and honored in the story of the widow’s mite (Luke 21:1-4) for anonymously giving all she had to serve God and others.

A formerly enslaved person blinded in one eye by an enslaver, Greeley arrived in Denver around 1879 or 1880 and was noted for freely giving of her faith, resources, prayer, and strength to all—regardless of race, ethnicity, or faith—until her death in 1918. When her meager resources as a domestic worker failed to provide, she begged for the needy, pulling a little red wagon containing food, toys, clothes, or even a mattress for someone in need. She never sought recognition for her acts of mercy and, sensitive to the possible negative consequences that might come to needy White people receiving assistance from a poor Black woman, she gave anonymously, leaving gifts at night.

A convert to Catholicism, Greeley was baptized at Sacred Heart Church on June 26, 1880. Neither poverty nor past trauma deterred her from evangelizing. Her devotion to the Sacred Heart (e.g., a Catholic devotion to Jesus’s love and compassion for all humanity) led her to attend daily mass at her parish Sacred Heart Church, pray for the Denver community, give alms to the poor, care for scores of children, sing in a small choir at Fort Logan, and specially minister to Denver’s fire fighters.

The Capuchin Franciscans of Denver recognized Greeley’s good works by accepting her into their fraternity as a secular Franciscan in 1901. She died in 1918 on the day of the Feast of the Sacred Heart (June 7) and was buried in the habit of the Third Order of Franciscans as Sr. Elizabeth of the Secular Franciscans. A Third Order is a group of unordained people who live by the ideals of a religious order. Jesuit Fr. Eugene Murphy said of Greeley, “Here was the secret of her influence. She had taken Christ literally, as had the Poverello of Assisi. Like him, she had given away all to the poor and had gone about making melody in her heart unto the Lord.”

At her funeral service, it took five hours for people from all walks of life to view her body and pay their respects. Denver organizations like The Julia Greeley Home for needy women continue to carry her name and mission.

Sources:

- Colorado Encyclopedia, Julia Greeley (History Colorado)

- Julia Greeley Guild, “Franciscans and Julia’s Cause”

- Denver Public Library, Genealogy, African American Western History Resources, “The First African American Coloradoan To Be Nominated for Sainthood”

Joann Stevens is a freelance writer and program specialist promoting unsung and unknown African American jazz, faith, and cultural innovators who have influenced democracy and racial justice for the Common Good.