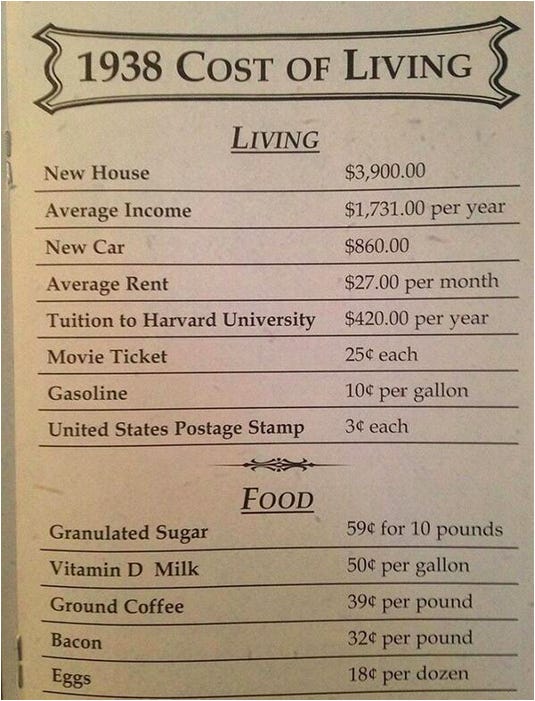

I was planning to write a short blog about the Silent or Traditionalist Generation, the name given to those born and coming of age between 1928 and 1945. They would follow the Greatest Generation and precede the Baby Boomers. To set the stage, I thought I would consider the cost of living in contrast to what it is today.

A loaf of bread was 10 cents or less. While Wonder Bread was a special treat, just having bread of any kind was a wonder during the Great Depression.

Thinking about bread, I began to search for photos that were taken of people during the Great Depression. There are a lot of photos of bread lines, but for the most part Black people are absent from these photos. I know from recorded history, as well as stories my own family told, that Black people were not the recipients of government programs created to ease the pain of economic hardship. It was as if White suffering was the tragedy of the times and Black suffering was business as usual—nothing new and, therefore, unworthy of sympathy or amelioration.

My family was in Memphis during these hard times, and though everyone suffered during the Great Depression, my people—in the specific and in the general sense—suffered a Greater Depression. In this time of great need, support was about who got fed first, and the prevailing rule was, “Last hired, first fired.”

Times were so hard that just keeping warm when the weather was cold was too much to expect. My Daddy’s mother lived in a literal shack in the Orange Mound community in Memphis. In a struggle to keep his mother and aunt from freezing, my Daddy, in his late teens and early twenties, would follow the train tracks to pick up pieces of coal that fell from the train cars and take them to my grandmother’s shack to fire the stove. One night, while scavenging for pieces of coal, someone with a shotgun shot my Daddy in the back.

As I recall how the old wound looked, the shot must have come from a distance and at an angle because it didn’t kill him. I could put my finger in the shiny sideways hole. My Mother used to get angry while telling the story about the pellets or buck shots that remained under Daddy’s skin.

I say that Black people experienced the Greater Depression because, while even low-level jobs were scarce for White people, they were non-existent for Black people who were not only trying to scratch out a living, but also trying to keep their heads down for fear of being lynched or enduring some other kind of cruelty. My family and other families of Black people who survived the Greater Depression truly are heroes.

These Silent Generation heroes would be inextricably tied to the spirit of the times of the Greater Depression. In them, one can sense the quiet strength and overwhelming desire to be and do more with the relative largesse following the Great Depression.

Much of what we know about Black history is the story of how the Silent Generation did not stay silent, taking action to change the trajectory of a people by organizing to fight for the civil rights of all people, training up the younger generation and seeing to it that their elders in the Greatest Generation, in particular, were afforded the rights and dignity too long denied them for their own contributions.

A few of the Silent Generation who raised their voices for civil rights:

- Martin Luther King, Jr. (b. 1929)

- Dorothy Cotton (b. 1930)

- Rupert Florence Richardson (b. 1930)

- Dick Gregory (b, 1932)

- Lola Hendricks (b. 1932)

- Andrew Young (b. 1932)

- James Meredith (b. 1933)

- Roy Innis (b. 1934)

- Bob Moses (b. 1935)

- Barbara Jordan (b. 1936)

- Diane Nash (b. 1938)

- Claudette Colvin (b. 1939)

- Julian Bond (b. 1940)

- Prathia Hall (b. 1940)

- Bernard Lafayette (b. 1940)

- John Lewis (b. 1940)

- Jesse Jackson (b. 1941)

- Kwame Ture (b. Stokely Carmichael, 1941)

- James Orange (b. 1942)