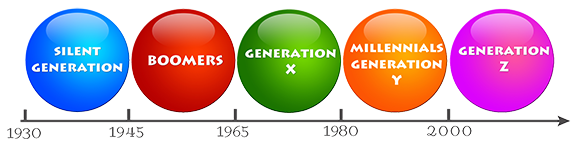

Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, Gen Zers. These labels have become popular ways to define generations. Before the common use of these labels, there wasn’t much public knowledge and discussion about who was born when and what their attitudes and values might be. Other than the term “Lost Generation,” the first popular label I recall is Baby Boomers. It was coined to describe the huge increase in population following WWII and the Korean War.

In addition to the term “Baby Boomers,” perhaps the publication that popularized the naming of generations was Tom Brokaw’s 1998 book titled The Greatest Generation. As a result of this book, there was a wave of nostalgia for war heroes and respect for patriots.

Naming generations promotes the idea that people born during an approximately 20-year span of time might have attitudes, characteristics, values, and sensibilities more similar to one another than to those born 20 years before or after. Because they experienced the same impactful events and presumably contributed to the spirit of the times in which they came of age, they may have a similar way of seeing the world and weighing the consequences of major changes in their environment.

As the naming of generations goes, I think that there is more integrity in the naming of Baby Boomers than the subsequent names given to generations. The label “Baby Boomers” is a short-hand description of the fact that there was a population surge during a particular span of time. The critical point I want to make is that the naming was based on a demographic fact that can be easily accessed.

It seems that the more recent generational names have creative hooks helping them to become sticky. These names capture the attention of those researching and writing about generations. The researchers begin with a hypothesis or an idea about what they think might be significant and distinctive about those born and coming of age during a particular time period. The name captures the interest of the public and over time enough people agree that this new generation is, indeed, different than any before.

I don’t think that there is anything wrong with the short-hand names for generational identity. What I wonder about is whether the names are not solely descriptive but are also prescriptive, and, therefore, could have an outsized influence on the way people see themselves.

The impact of the generational naming will not be the same for all within the designated group. However, some may adapt their attitude and lifestyle to the descriptions they hear about their group. They appropriate the descriptions as guides to understand and define their sense of self rather than relying on their personal experiences, unique backgrounds, special characteristics and, most of all, their own sense of agency.

Seeing oneself through the prism of how one’s generational cohort is described may allow one to take less responsibility for internal reasoning and personal control. Those who see themselves this way may get a pass for the way they react to their environment, and the way they respond to their life’s circumstances because there is consensus that the events that occurred during their time of development have influenced their way of interacting with the world, their way of being.

In conversations with people who are not Millennials or Gen Zers, it’s common to hear excuses for behaviors that may not have been seen as acceptable by past generations. With a metaphorical shrug, members of a particular generation are given a pass, attributing their behavior to their generation and not to the individual. Individuals are not responsible because they are influenced by events beyond their control. Rather than being held accountable, they are supported at best and pitied at worst.

As I come to the close of my thinking on this, it seems that generational labels and naming of signs in astrology have similarities. Both rely on the time of birth to ascribe characteristics or traits. Both are ostensibly descriptive but for some are prescriptive. Just as there are skeptics about astrology, I think there might need to be more skeptics about naming and describing generations, especially when the names come before some of the cohort comes of age.